Honestly, it is a bit ridiculous to compare Postgres and ClickHouse. The two database solutions are as similar as grapes and grapefruit. ClickHouse was created for a specific purpose; PostgreSQL (aka Postgres) was designed to be flexible and all-purpose.

So why even compare them? Because most companies that invest in an online analytical processing (OLAP) database like ClickHouse originally used an online transaction processing (OLTP) stack like MySQL or Postgres. PostHog's database journey was no different.

In 2020, PostHog used Postgres to store client data. In the beginning, it worked. But usage grew very, very fast. Eventually, that all-purpose Postgres database was tasked to store millions of rows of data. It was obvious Postgres couldn't handle the scale necessary for an analytics platform like PostHog.

At first, the team tried a ton of hack-y and wacky solutions in attempts to get Postgres to work. Turns out, that wasn’t sustainable (who would’ve thought!). Eventually, PostHog migrated client data to ClickHouse. Boom!

This is what that felt like...

Suddenly, all those data problems were solved, Thanos-snapped from existence. Here, we’re diving deep into how and why ClickHouse saved the day.

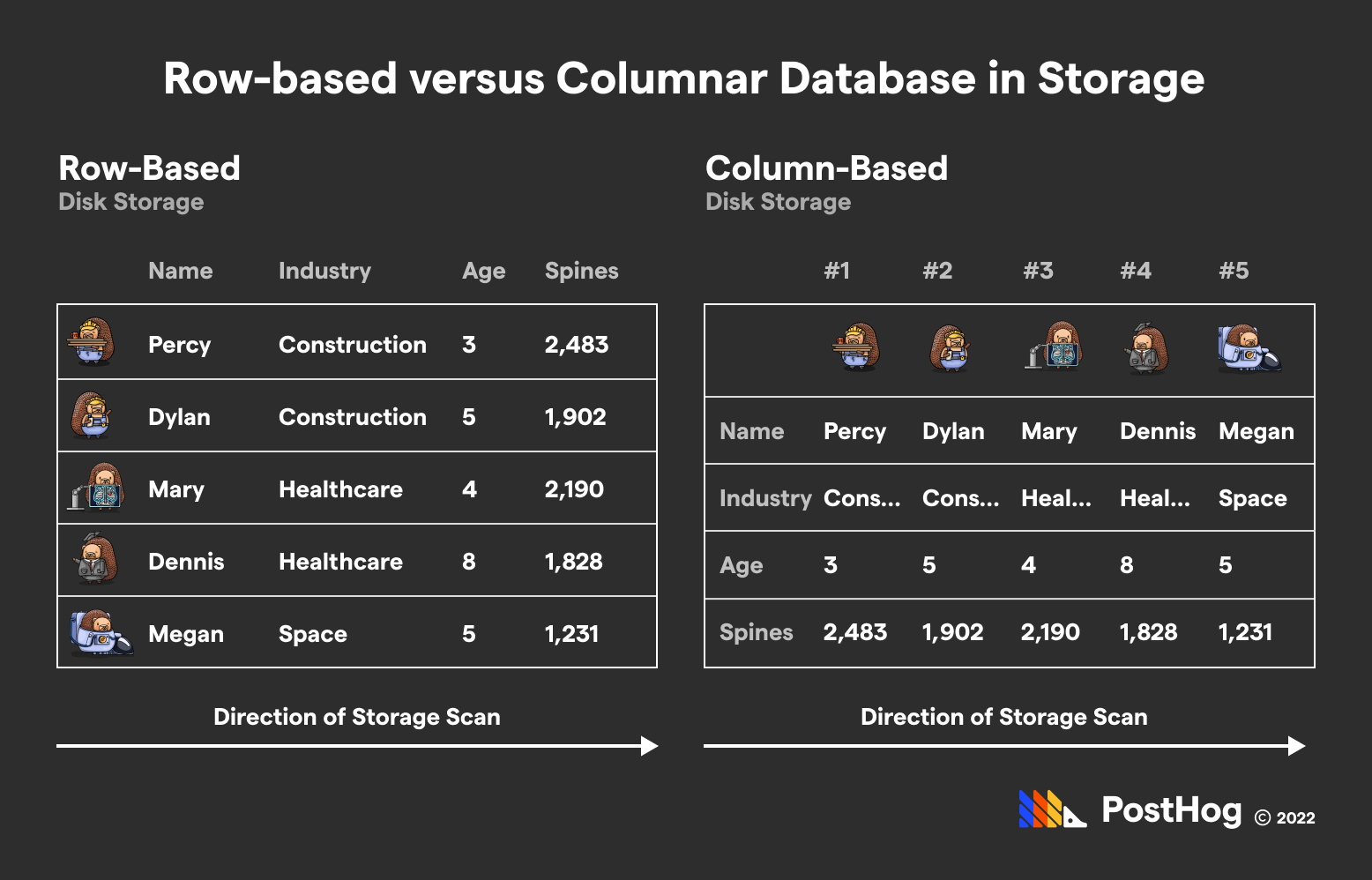

If you’ve ever taken a databases 101 course, you’ve likely heard lectures on row-based relational databases. Good chance, the professor referred to them as simply relational databases or even normal databases.

The majority of popular solutions — MySQL, Postgres, SQLite — are all row-based. In each of these, data / objects are stored as rows, like a phone book.

In contrast, ClickHouse is a columnar database. ClickHouse tables in memory are inverted — data is ingested as a column, meaning you’ve a large number of columns and a sizable set of rows.

Here's what that looks like...

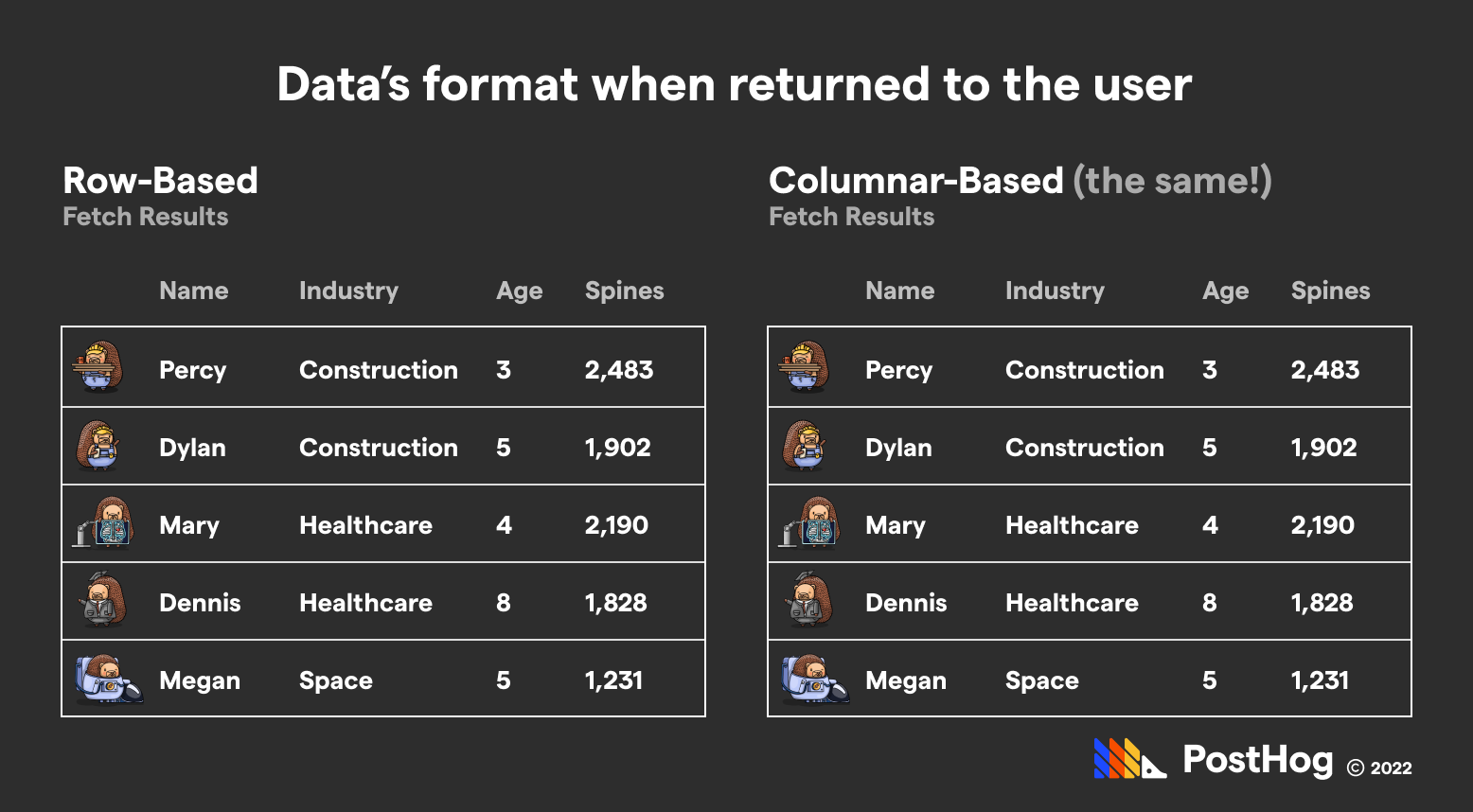

The difference – to be clear – is how the data is stored; to the user, no mental-inversion is needed. You still deal with tables with entries. You continue to utilize SQL to interface with ClickHouse. The big difference is that those queries perform differently from the analog queries in Postgres or other row-based relational database.

ClickHouse was designed for products that require fetched aggregate data, such as analytics, financial real-time products, ad-bidding technology, content delivery networks, or log management. Basically, it’s for data that doesn’t need to be changed; ClickHouse is downright terrible at mutations.

It’s important to realize that ClickHouse is rarely used alone. Because ClickHouse is bad at update-heavy data, it’s not a great database to run the day-to-day usage of an app. If ClickHouse powered Tinder, the only match users would have is with a loading modal. Anyone who uses ClickHouse is also using Postgres or another rows-based relational database for the non-specialized bits of their product.

One previously-used analogy to compare OLTP databases (Postgres) with OLAP databases (ClickHouse) is Teachers vs Principals. A teacher (akin to Postgres) would be able to efficiently answer the question “How is Johnny, the 4th grader, doing in Math?”. A principal (akin to Clickhouse) wouldn’t know who Johnny is, but would be able to quickly provide the student body’s national exam pass rate.

Let’s start with some obvious uses cases that sharply lean towards Postgres or ClickHouse.

A Simple Case where Postgres is used over ClickHouse: You operate a dating app and need to change Employer in a John Doe’s row.

Postgres would do this seamlessly: access John Doe’s row (including his other attributes), alter the Employer value and write. What about ClickHouse? Well, it would need to load every Employer value for every entry, go to John Doe’s index, alter it, and write the entire “column” back into data.

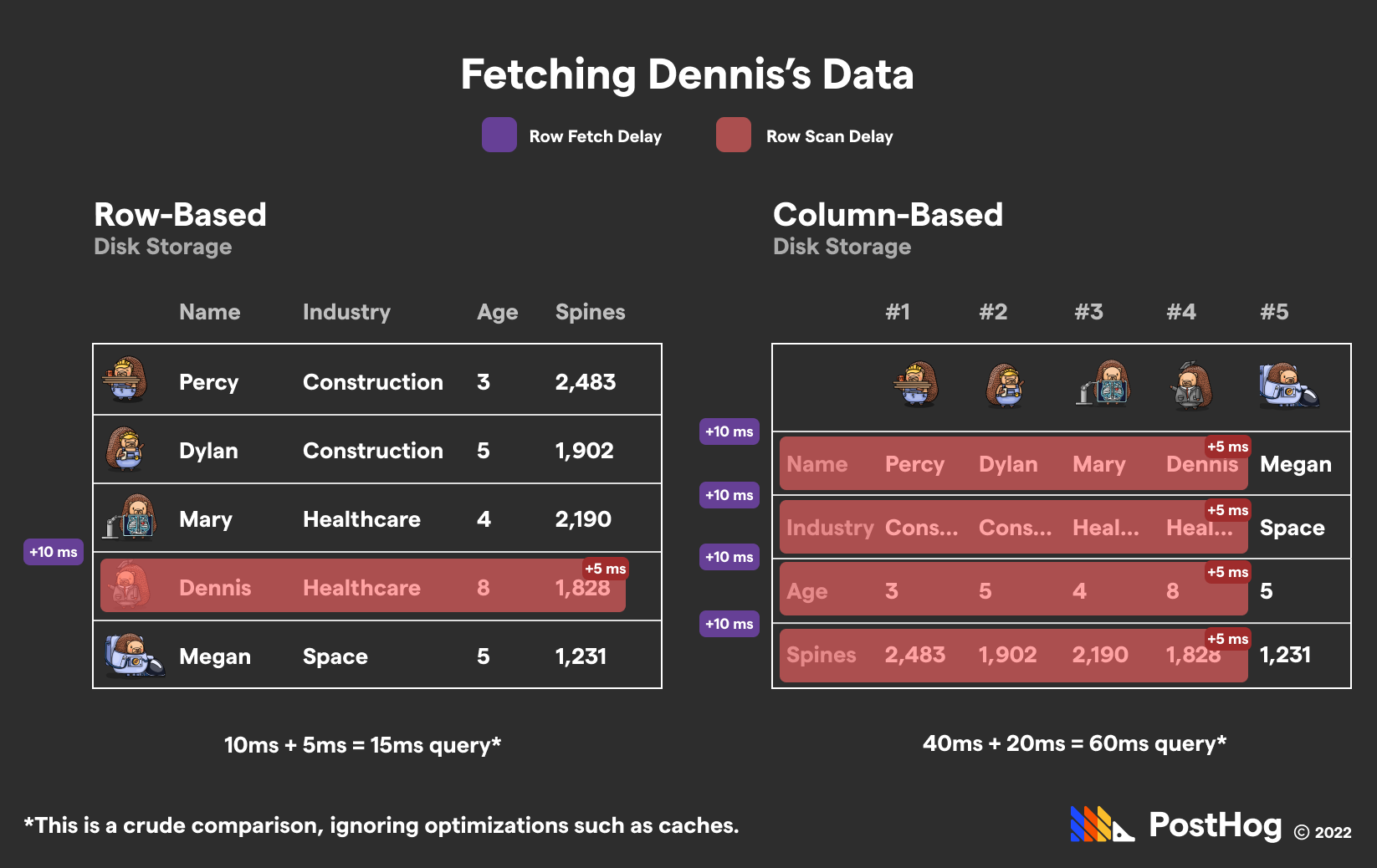

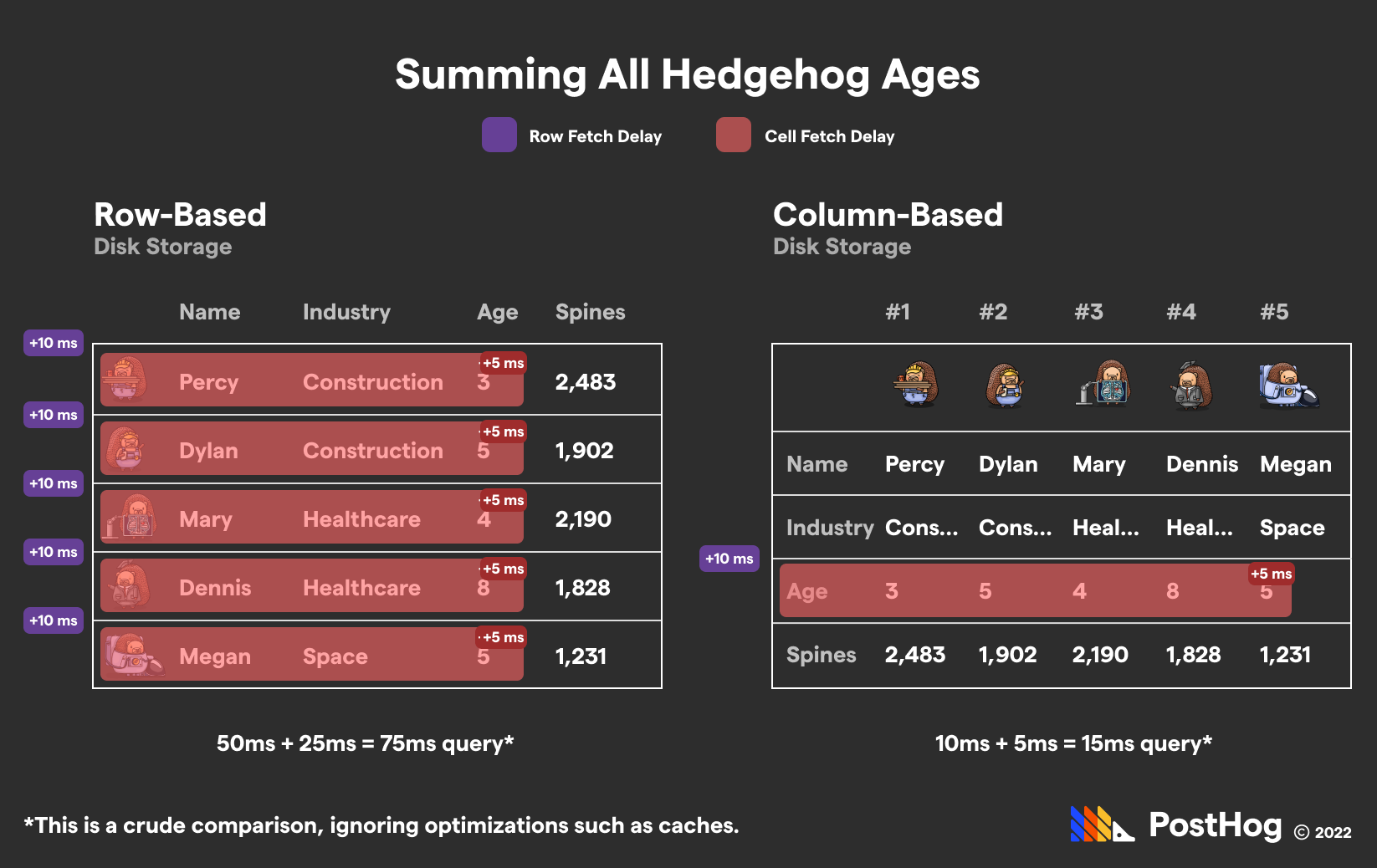

Let’s analyze Postgres vs ClickHouse with a (very simplified) hedgehog database. Crudely, we can visualize why Postgres crushes ClickHouse when fetching a single hog’s data:

A Simple Case where ClickHouse crushes Postgres: You operate a financial transaction startup and need to calculate the average transaction price across billions of entries.

Postgres would need to incrementally retrieve every entry, grab the transaction price, add it to a running total, and return the value. ClickHouse meanwhile could calculate this, without any additional caches or optimized engines, with a single read.

If we were to extend the previous hedgehog database, this query looks a little like this:

This is, again, a crude comparison. It ignores caches on both ends, and more interestingly, PostHog’s optimizations under-the-hood, such as:

Fetching data in a single read because of the columnar format.

Parallelizing requests maximizing CPU efficiency by grouping, then merging data via vectorized query execution.

Utilizing specialized merge-tree engines with significant optimizations.

No transaction-locking overhead.

Robert Hodges, CEO of Altinity, once compared ClickHouse to a drag-racer — it might not have doors, but it is incredibly, incredibly fast when used correctly.

These optimizations are made possible by ClickHouse’s insert-and-optimize-later philosophy. ClickHouse is constantly merging data in the background to collapse series of data into single values to expedite future queries.

Because ClickHouse doesn’t expect mutation requests, it can depend on merges because the individual data won’t be changed; by extension, aggregate values won’t need to be recalculated.

Because ClickHouse is the more opinionated solution, comparisons between Postgres and ClickHouse tend to go:

ClickHouse does X really well, but Postgres can achieve it with Y, Z, and D modifications with A & B set-backs.

Conversely, you will also see:

Postgres can do X just fine, and ClickHouse could X as well if you’re okay with melting your server.

It’s like comparing a MacBook (Postgres) with a music synthesizer (ClickHouse) — you can make decent music on your Macbook, but you explicitly can’t run Microsoft Excel on a synthesizer.

Likewise, it should be no surprise that most of this section will focus on the former scenario (hacking Postgres to operate like ClickHouse). The converse is simply ridiculous.

There are other projects that have hacked Postgres into an OLAP database that may serve as more apt comparisons to Clickhouse—notably Citrus DB, TimescaleDB, AWS Redshift, and Greenplum. However, those projects are databases in their own right, and my goal is to explain the differences between the generalized Postgres and a single specialized OLAP solution.

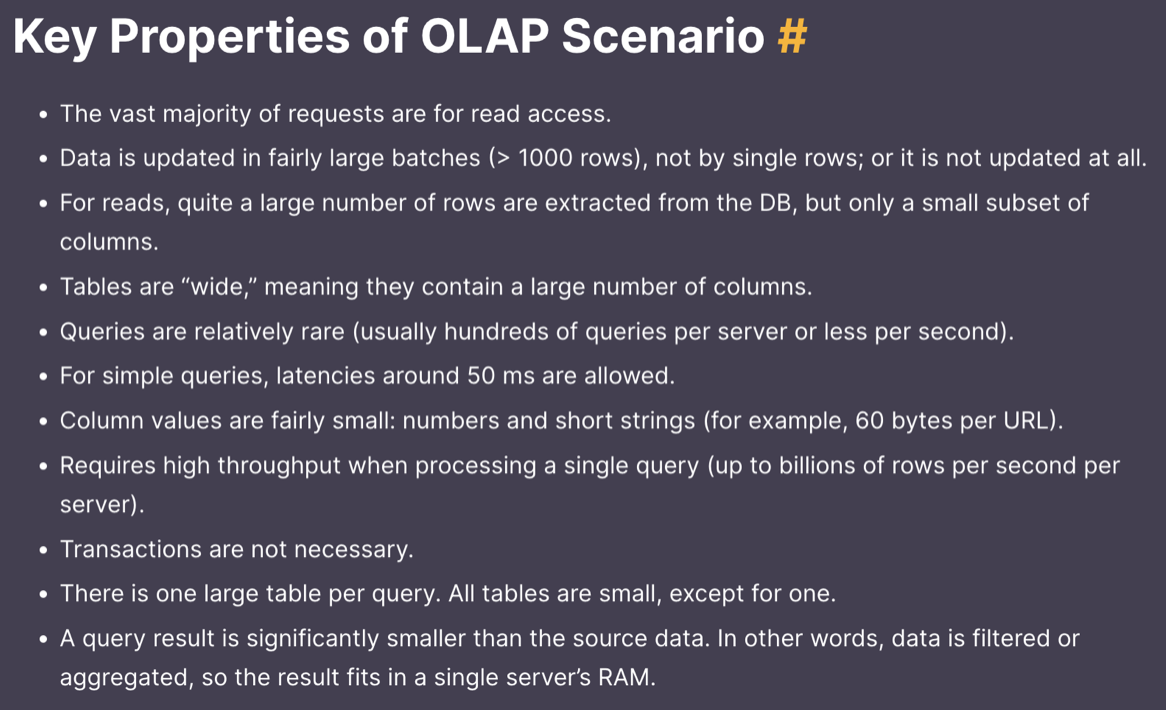

ClickHouse’s documentation is a tad confusing to readers unfamiliar with OLAP databases. This is because ClickHouse makes usage recommendations based on the reader’s expected goals.

Let’s take a look at ClickHouse’s self-stated key properties:

ClickHouse states that a vast majority of requests should be for read access, but this is a bit misleading — it’s more that read-heavy requests should greatly outnumber update/mutation requests, not inserts.

ClickHouse states that inserts should happen in batches. This is not because ClickHouse is bad at write-access; rather, batched inserts take advantage of ClickHouse’s core tenet of “insert fast, optimize later” philosophy. Non-batched requests are inherently slower than batched counterparts, and relatively the same when the database doesn’t support transactions.

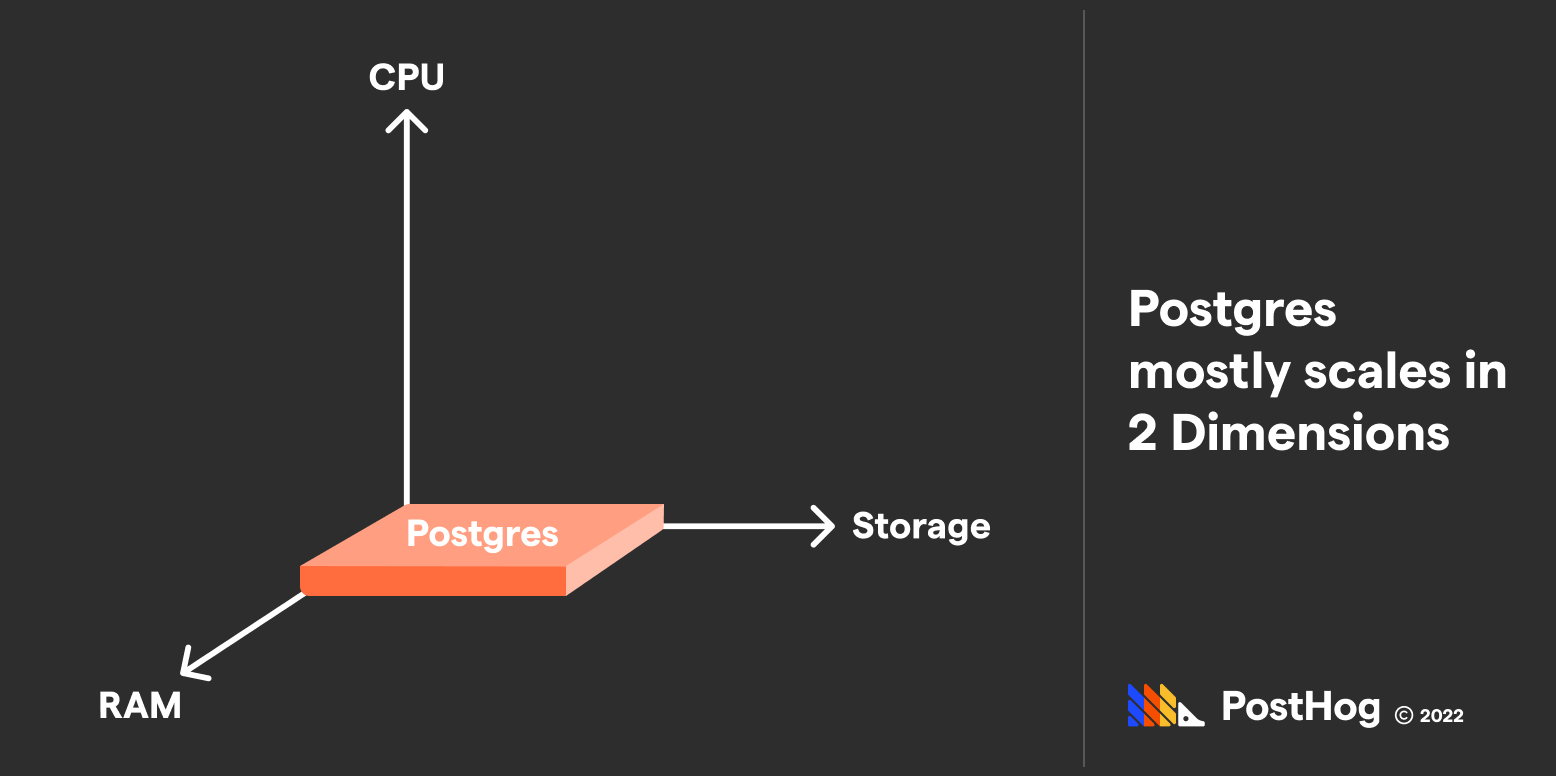

When evaluating infrastructure resources, we typically think about CPUs, RAM, and Attached Storage. This is a great place where ClickHouse and Postgres differ.

For Postgres, RAM and Attached Storage obviously matter, but the CPU count has limited benefits. Since 2016, Postgres can parallelize certain computations (rather inconsistently), but is primarily a single-process product, as the below shows:

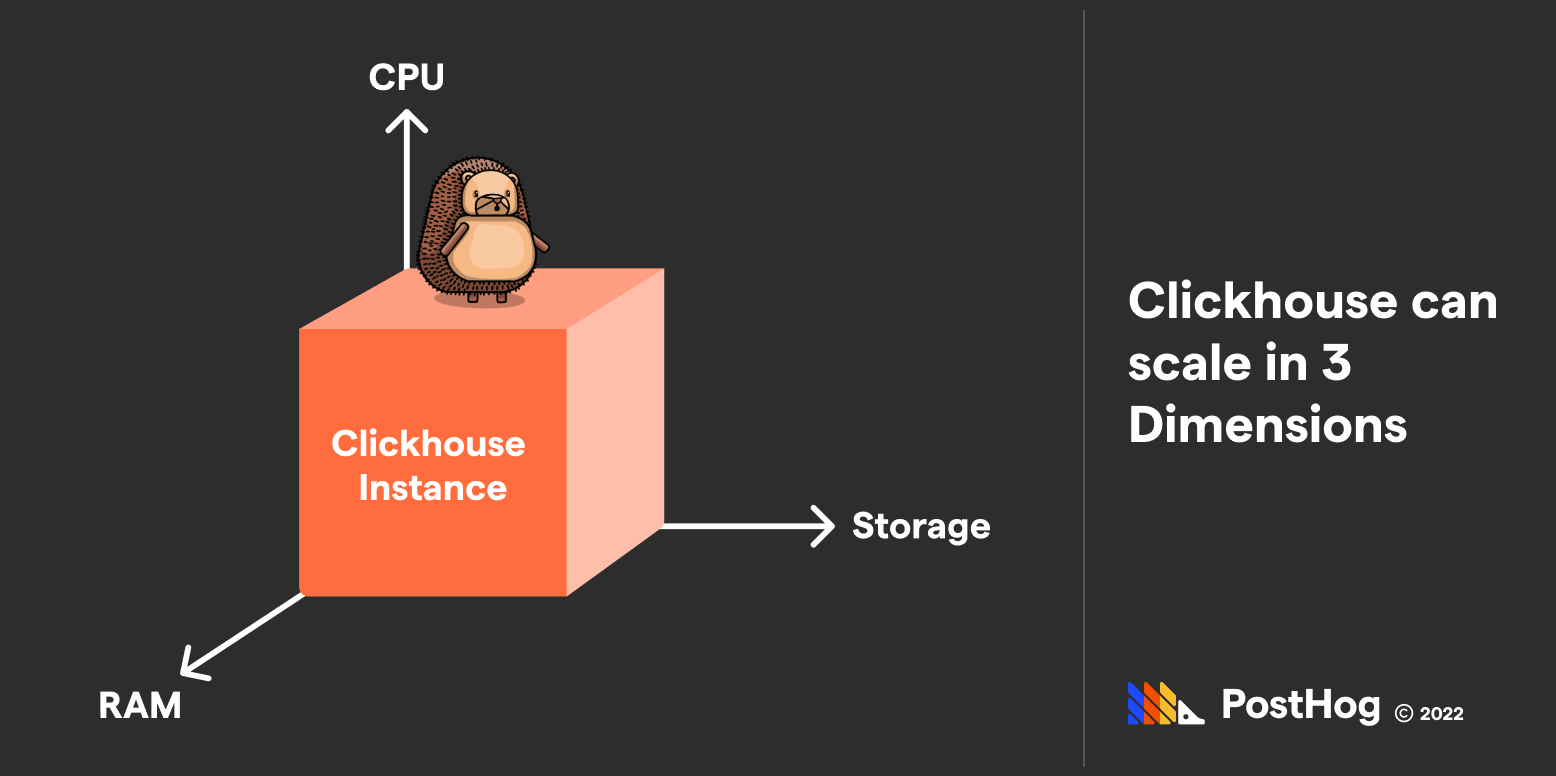

ClickHouse, meanwhile, is all about silently optimizing data and optimizing data in parallel. You can scale the power of your ClickHouse instance’s performance by improving any three of those dimensions, including CPU.

An optimized ClickHouse instance can function so fast that a bulk of a query’s wait-time from a frontend perspective is a function of network speed, not data retrieval.

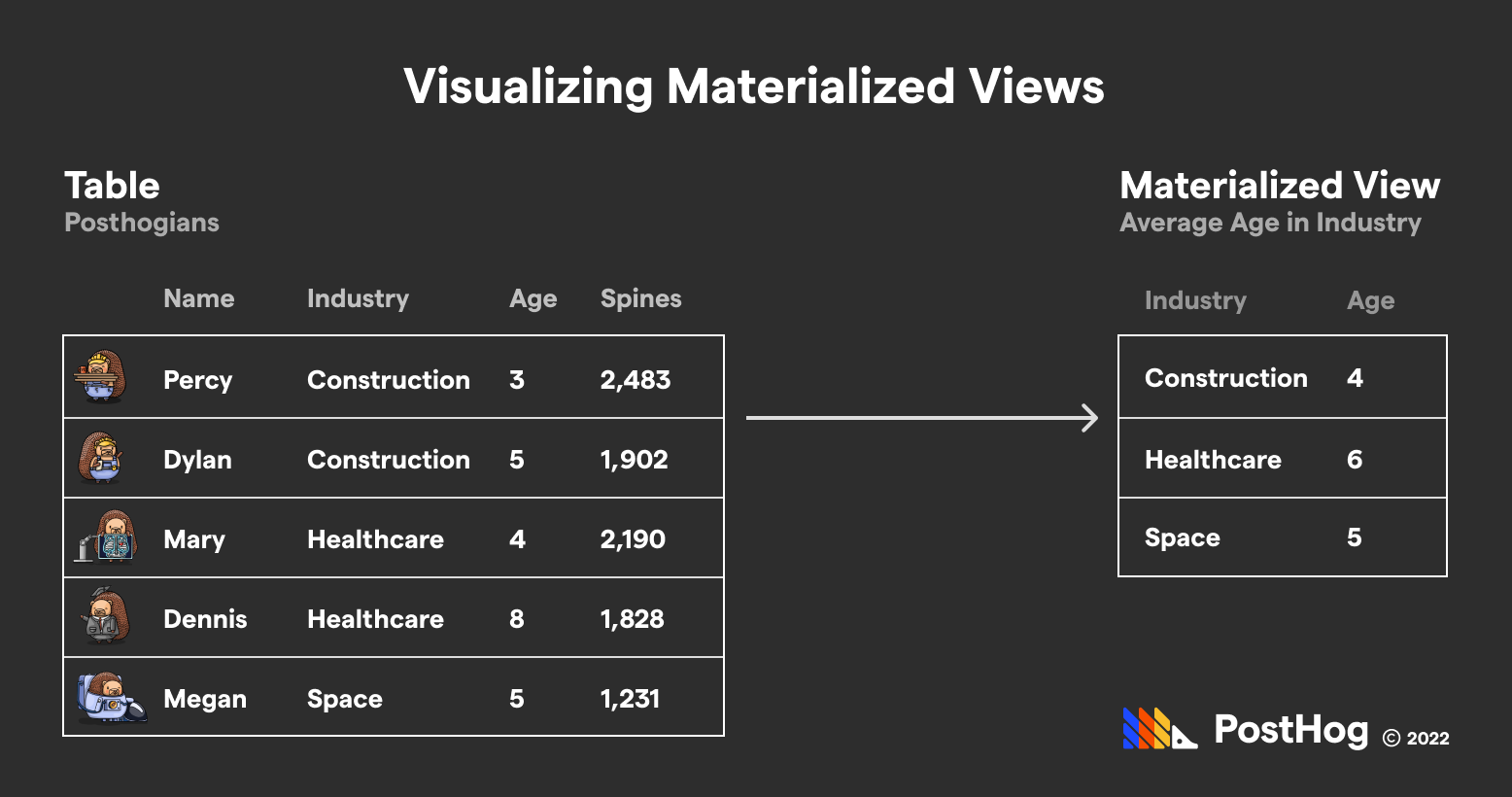

Materialized Views compose arguably the biggest area where ClickHouse differentiates from Postgres.

What is a Materialized View? Unlike a normal view, which is basically a saved SQL query that re-executes at runtime to expose an ephemeral table to query from, a materialized view is a derived independent table that is generated at some specific point of time.

Imagine you’ve abandoned your dating app and banking businesses; now, you run a lovely education non-profit. You need to constantly query the median test score from your database — you could construct a Materialized View that stores median test scores by grade level. Then, when you need to access those test scores, you can query the Materialized View and access the results without re-calculating the median scores.

Here’s a version using our previous simple hedgehog database:

Both Postgres and ClickHouse have functionality to build Materialized Views; the fundamental difference is that Postgres’s Materialized Views need to be manually re-updated, whereas ClickHouse automatically updates them. For some cases, like test scores, this can be done once, after all the tests are uploaded; for others, like website analytics, an auto-update materialized view like ClickHouse’s is necessary.

ClickHouse can only accomplish auto-updates efficiently because of its insert-and-optimize-later philosophy. ClickHouse never sleeps — it uses its idle time to compress data in Materialized Views so that future data look-ups are fast and efficient.

But it’s more than just time-allocation. For instance, if you need to add numbers to produce aggregate results, ClickHouse’s SummingMergeTree engine will dramatically parallelize the process. Alternatively, if you need to average data, the AggregatingMergeTree is your dear friend.

Ironically, the more interesting topic in Materialized Views is not how ClickHouse efficiently updates them — that is the bread and butter of its purpose — but if Postgres can be hacked to achieve something similar.

Here are some strategies on how Postgres can emulate automatic Materialized View updates alongside their downsides:

- Fast Refresh Module. By blending a static Materialized View and a running log of changes, Postgres’s Fast Refresh Module can simulate an automatically-updated Materialized View. The downsides are that utilizing a log is incompatible with certain fetch requirements (e.g. count), high-write databases could overwhelm the log, and that logs slow down a fetch query.

- Triggers. You could set a Postgres trigger to refresh a Materialized View on page load. This solution will rarely work unless you have seldom write operations; refreshing the Materialized View completely wipes the original result and will likely bludgeon the CPU.

In a nutshell, Postgres can be bandaged up to achieve some efficiency that ClickHouse boasts around Materialized Views, but fundamentally, ClickHouse treats Materialized Views as an out-of-the-box benefit with efficiency and simplicity as cornerstone value props.

Technically, database engines are nothing new. MySQL has plenty of engines, although it is typically used with just InnoDB. Postgres technically only operates using a single engine, though the Postgres team is building a new engine called zheap, specifically designed to optimize the UPDATE function.

For ClickHouse, engines are a core feature. ClickHouse should be instructed to utilize a specialized engine depending on your data needs, and that engine could dramatically optimize results. Notably, different materialized views could have different engines, such as AggregatingMergeTree() or SummingMergeTree(), form-fitted to that materialized view’s purpose.

ClickHouse also has specialized engines — MaterializedView, Merge, Dictionary etc. — that are used ephemerally to move, merge, or export data. For instance, the MaterializedView engine is able to create a new materialized view much faster than a generalized engine (not to operate it, however; the materialized view will utilize its own engine).

Clickhouse's engines utilize vectorized execution, originally championed by the MonetDB team. Vectorized query execution batches data to achieve bulk processing. While there are some third party Postgres extensions to achieve a similar effect, ClickHouse is built around it, processing data on every CPU while better utilizing the CPU cache and SIMD CPU instructions.

One of the biggest constraints of Postgres for the longest time was sharding. Even now, Postgres’s most-used sharding solution — declarative table partitioning — isn’t exactly a sharding solution as the splitting operates at a table-by-table level.

If you want to truly shard a table in Postgres, you must utilize Postgres’s Foreign Data Wrapper (FDW) to achieve it. But this adds considerable overhead and is argued to be a lackluster sharding solution. Notion notably took months to implement a robust sharding solution for Postgres.

ClickHouse’s approach to sharding is a bit different and more fleshed out. Upon sharding, ClickHouse creates an umbrella table that knows the locations of the shards and replicas, which will be utilized to do a federated query across an entire data set. Do note that ClickHouse does break its single-binary C++ commitment once sharding goes into effect because it utilizes Apache Zookeeper to manage the shards.

Sharding can be done prematurely to optimize performance. When multiple ClickHouse shards exist, in true ClickHouse fashion, each shard can parallelize queries expediting end results. However, for faster queries, network latency may trump the parallelization benefits.

ClickHouse was made to handle lots and lots of aggregate data. While starting with Postgres may be acceptable for the early days of a data-heavy business, platforms like ClickHouse are the better investment when aggregate fetches come into play.

ClickHouse optimizes data aggregating at every layer — inception, storage, caching, and returning — and will boast 1000x advancements over tools like Postgres. However, ClickHouse can rarely be used in isolation, as many day-to-day needs of an application are too update / single-line-read heavy to utilize a columnar database.